If living a surrealist life is possible, Juanita Guccione (1904-1991) did so and documented it in her paintings from the 1940s. Eighteen works at Lincoln Glenn teem with remarkable stories and visions. Roughly half the paintings are signed “Marbrook,” an Anglicized version of her Algerian first-husband’s last name, Marbrouk, and others are signed “Guccione,” her second husband’s surname, as if two artists were on display instead of just one visionary painter.

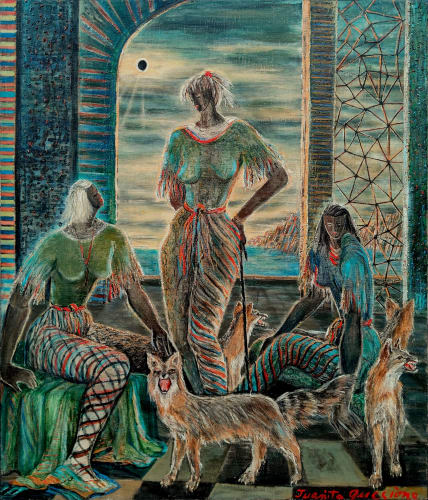

The canvases here are dreamlike, sometimes joyful, sometimes disturbing. Guccione lived for a time with the female dancers of the Ouled Naïl tribe in Algeria, and there are women dancing and posing in her work. Several paintings feature stiff-looking birds and animals that came from her second husband’s taxidermy shop in Woodstock, N.Y. Ropes and nautical motifs echo her experience working at the Brooklyn docks in the 1930s, while “War Gadgets” (1943) has a giant ship turned upside down in the water, reflecting a world in conflict. Later, Guccione turned to esoterica, including tarot and Theosophy — alternative forms of spirituality that made their way into new age thinking — and these appear in her paintings as well.

Over the past several years there has been a reassessment of the contributions to surrealism made by women. Exhibitions and books have been devoted to figures like Remedios Varo, Leonor Fini, Leonora Carrington, Kati Horna, Suzanne Césaire and, of course, Frida Kahlo. There is also a wave of current surrealist-style painting by younger female and nonbinary artists who use dreamlike narratives and juxtaposing images to process their lives. In this context, Guccione’s decades-old paintings look startlingly fresh.