Works

Biography

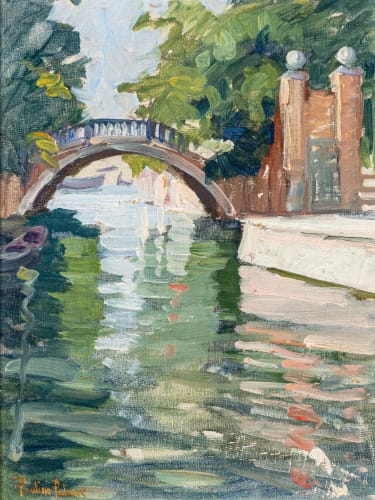

Pauline Palmer (née Lennards in McHenry, Illinois 1867 - Trondheim, Norway 15 August 1938) was one of Chicago's early twentieth-century portrait and landscape painters who became one of the Midwest's most active and energetic exponents of impressionism. Palmer's father, Nicholas Lennards, a Woodstock, Illinois merchant, encouraged her to pursue art. Pauline studied at the Art Institute of Chicago between 1893 and 1898, including a one-month session with William Merritt Chase in 1897, and further temporary instruction with Frank Duveneck. In 1899, her work was compared to that of Chase: "She draws well, her colors are true and values well rendered; all the result of persistent and careful study." (M. M., 1899, p. 217). Later that year, Palmer enrolled in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Colarossi in Paris, where Raphaël Collin was one of her teachers, and studied privately with Richard Miller. She made her debut in the Paris Salon of 1903, on which occasion Guillaumina Agnew wrote about Palmer's popularity in The Sketch Book (July 1903): "Mrs. Palmer was the favorite among all the American artists here. . . ." At the St. Louis Universal Exposition, Palmer won a bronze medal for three works, one of which, The White Shawl, was illustrated in Paul Schulze's memorial article in 1939. An elegantly dressed woman is reading, seated in a profile pose that recalls paintings by Mary Cassatt. Later in 1915, at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, her painting The Ledge was on view.

Bulliet (1936) noted how Palmer's portrait of a Spanish boy, Rojerio was compared to works by Goya, therefore praised highly. She continued to have paintings accepted for exhibition in the Salons until 1911. Indeed, Palmer's exhibition record is phenomenal and she won an impressive number of awards. At the Art Institute of Chicago between 1896 and her death, she exhibited more than 250 works. That museum has two of her works: After the Rain (ca. 1910) and Provincetown (1926). Although Palmer traveled extensively, she remained an integral member of the Midwest's art community. During her distinguished career, she would become the first woman president of the Chicago Society of Artists (1918 to 1929). Having returned from Paris to America, Palmer met the celebrated opera star, Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861-1936) at the Appleton, Wisconsin music festival. In 1912, the diva called on Palmer to execute portraits of her children at her home in Caldwell, New Jersey. Records at the San Diego Museum of Art show that Schumann-Heink's portrait was formerly in their collections, then de-accessioned. Bulliet tells the colorful story of this commission and how Palmer managed to get the restless boy to sit still for his portrait.

Palmer's earliest works have a lingering Barbizon School look, with somber tones and an unsystematic use of broken color. Later her palette became lighter as she grew more bold in the application of pigment, created less rigid compositions, but finally she abandoned the plein-air manner for a Fauve-like expressionism. Palmer never stopped learning: after her career was well established, she moved to Provincetown and studied with Charles Hawthorne. There, she enjoyed painting Portuguese children. One of her Provincetown works is the delightful interior scene called The Artist's Studio (Private collection; see Seckler, 1977, p. 153). Despite her inquisitiveness and the loosening up of her technique, Palmer was considered to be a foe of modernism (Bulliet, 1935). In 1923, she left the Chicago Society of Artists after works by three abstract artists were accepted for the annual exhibition. Palmer formed the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, which represented the more traditional wing of the Chicago Society of Artists who followed her (Bulliet, 1939). One CSA painter she could not accept, and with whom she continued to feud in P-Town, was Flora Schofield (1873-1960), who started in Hawthorne's Cape Cod School of Art then joined the modernist wave by studying under Albert Gleizes and André Lhote in Paris, then with B. J. O. Nordfeldt in Provincetown. Fiercely cosmopolitan, and an opponent of regionalism, Flora Schofield developed her own representational style tinged with cubism.

At her death in 1938, Palmer was called "one of the leading woman painters in America." (New York Times obituary, 16 August 1938). The Art Institute of Chicago organized a memorial exhibition, which opened in the following year, and in the summer of 1950, the Art Institute issued two $750 prizes bearing Palmer's name. Gerdts (1990) praises Palmer as "one of the earliest and finest" Chicago outdoor figure painters who worked in the impressionist aesthetic.

Bulliet (1936) noted how Palmer's portrait of a Spanish boy, Rojerio was compared to works by Goya, therefore praised highly. She continued to have paintings accepted for exhibition in the Salons until 1911. Indeed, Palmer's exhibition record is phenomenal and she won an impressive number of awards. At the Art Institute of Chicago between 1896 and her death, she exhibited more than 250 works. That museum has two of her works: After the Rain (ca. 1910) and Provincetown (1926). Although Palmer traveled extensively, she remained an integral member of the Midwest's art community. During her distinguished career, she would become the first woman president of the Chicago Society of Artists (1918 to 1929). Having returned from Paris to America, Palmer met the celebrated opera star, Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861-1936) at the Appleton, Wisconsin music festival. In 1912, the diva called on Palmer to execute portraits of her children at her home in Caldwell, New Jersey. Records at the San Diego Museum of Art show that Schumann-Heink's portrait was formerly in their collections, then de-accessioned. Bulliet tells the colorful story of this commission and how Palmer managed to get the restless boy to sit still for his portrait.

Palmer's earliest works have a lingering Barbizon School look, with somber tones and an unsystematic use of broken color. Later her palette became lighter as she grew more bold in the application of pigment, created less rigid compositions, but finally she abandoned the plein-air manner for a Fauve-like expressionism. Palmer never stopped learning: after her career was well established, she moved to Provincetown and studied with Charles Hawthorne. There, she enjoyed painting Portuguese children. One of her Provincetown works is the delightful interior scene called The Artist's Studio (Private collection; see Seckler, 1977, p. 153). Despite her inquisitiveness and the loosening up of her technique, Palmer was considered to be a foe of modernism (Bulliet, 1935). In 1923, she left the Chicago Society of Artists after works by three abstract artists were accepted for the annual exhibition. Palmer formed the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, which represented the more traditional wing of the Chicago Society of Artists who followed her (Bulliet, 1939). One CSA painter she could not accept, and with whom she continued to feud in P-Town, was Flora Schofield (1873-1960), who started in Hawthorne's Cape Cod School of Art then joined the modernist wave by studying under Albert Gleizes and André Lhote in Paris, then with B. J. O. Nordfeldt in Provincetown. Fiercely cosmopolitan, and an opponent of regionalism, Flora Schofield developed her own representational style tinged with cubism.

At her death in 1938, Palmer was called "one of the leading woman painters in America." (New York Times obituary, 16 August 1938). The Art Institute of Chicago organized a memorial exhibition, which opened in the following year, and in the summer of 1950, the Art Institute issued two $750 prizes bearing Palmer's name. Gerdts (1990) praises Palmer as "one of the earliest and finest" Chicago outdoor figure painters who worked in the impressionist aesthetic.

Press

Exhibitions

Enquire