-

Study for Ladders, 1948

Study for Ladders, 1948 -

War Gadgets, 1943

War Gadgets, 1943 -

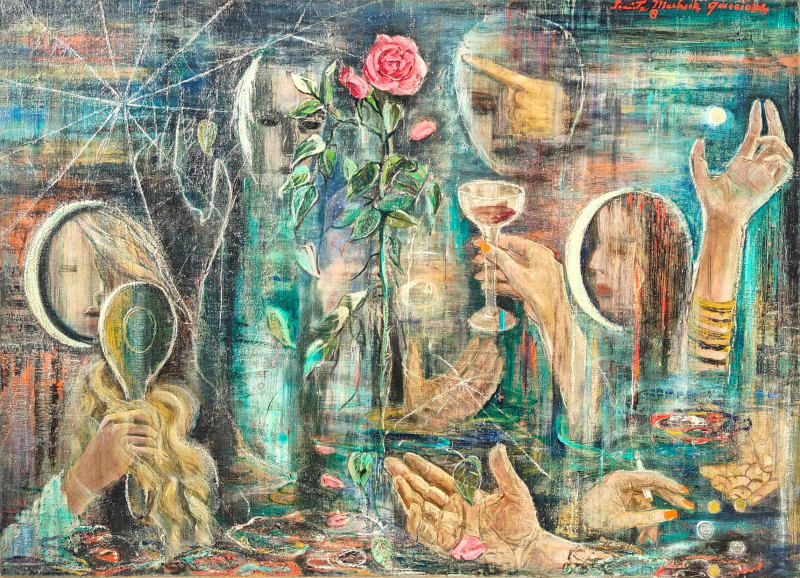

Lesson from the Rose (Whither my Destiny), 1940s

Lesson from the Rose (Whither my Destiny), 1940s -

The Race, circa 1951

The Race, circa 1951 -

Dancer by the Sea, circa 1946

Dancer by the Sea, circa 1946 -

And The Sun Too Shall Fade Away, 1948

And The Sun Too Shall Fade Away, 1948 -

Stubborn Horse II, circa 1952

Stubborn Horse II, circa 1952 -

Don't Be So Sure, II, circa 1991

Don't Be So Sure, II, circa 1991 -

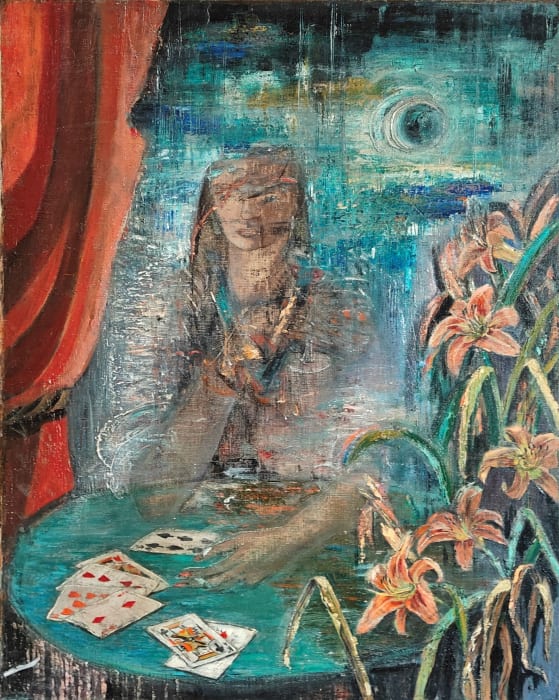

The Dealer, circa 1945

The Dealer, circa 1945 -

Passport, circa 1949

Passport, circa 1949 -

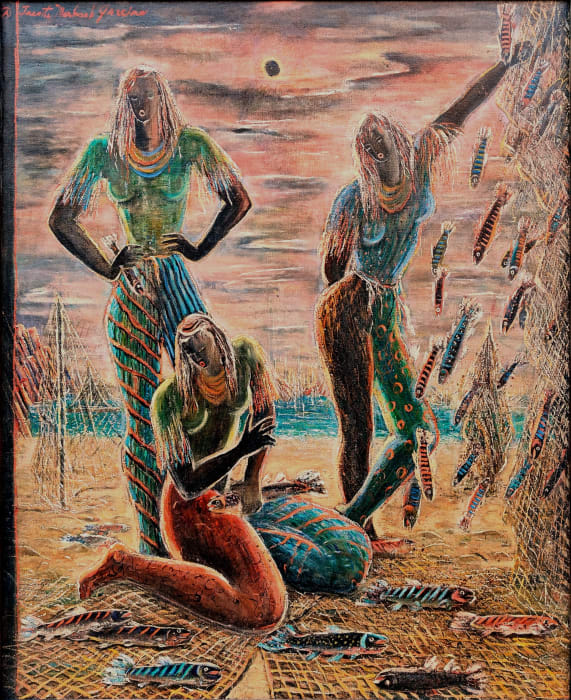

A Good Catch, circa 1947

A Good Catch, circa 1947 -

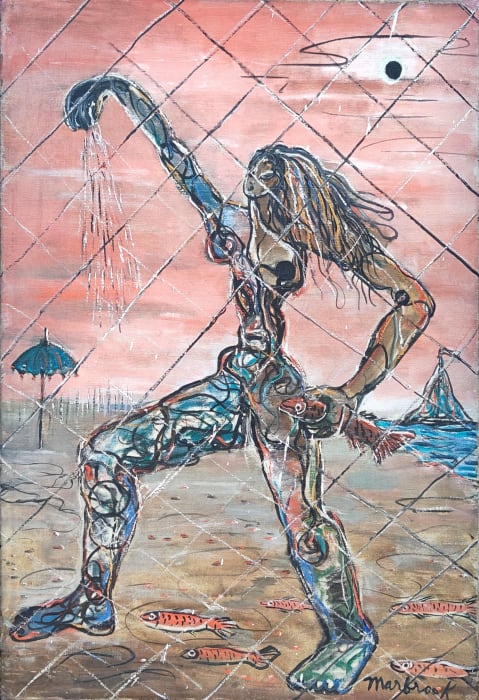

Woman with Fish, circa 1946

Woman with Fish, circa 1946 -

Betty and Her Pet

Betty and Her Pet -

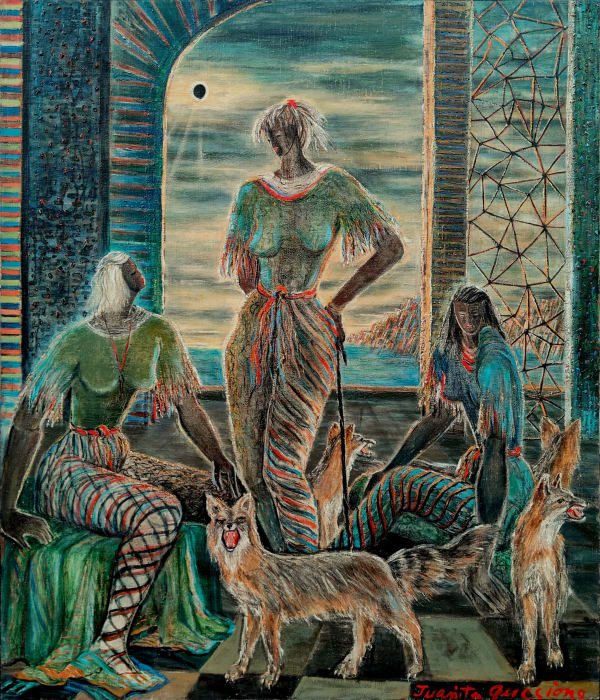

Ill Wind from Europe, 1936

Ill Wind from Europe, 1936 -

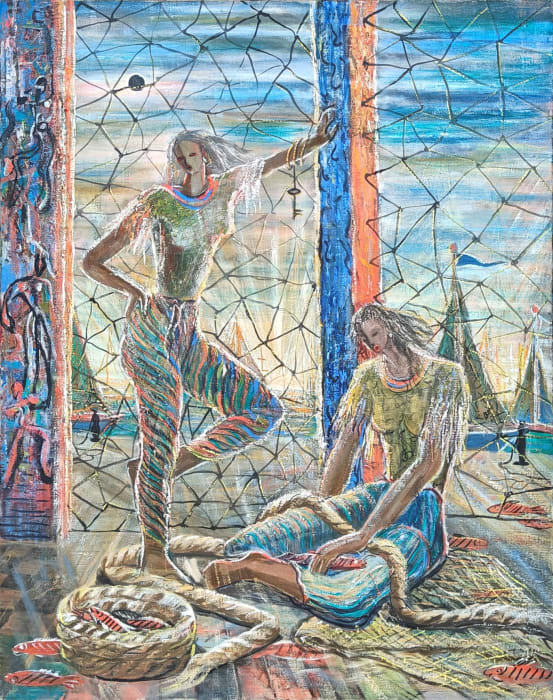

Untitled (two women, nets, coil of rope), circa 1946

Untitled (two women, nets, coil of rope), circa 1946 -

Brothers, circa 1949

Brothers, circa 1949 -

Plateau, circa 1946

Plateau, circa 1946 -

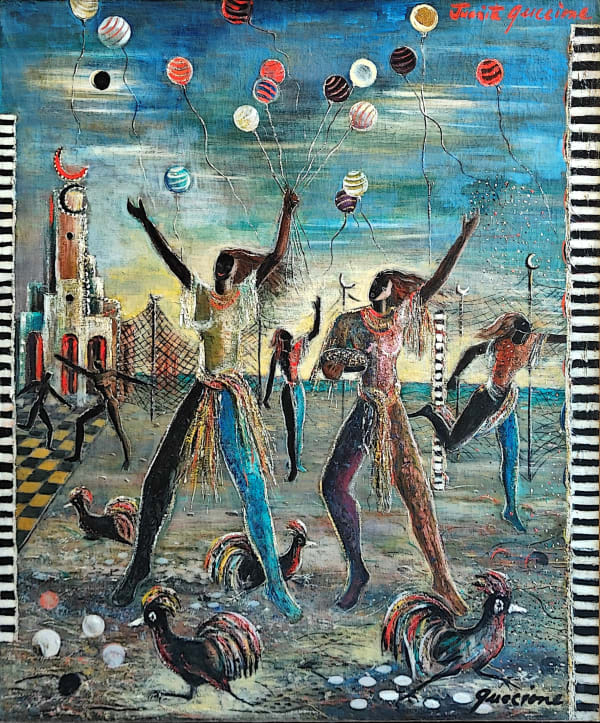

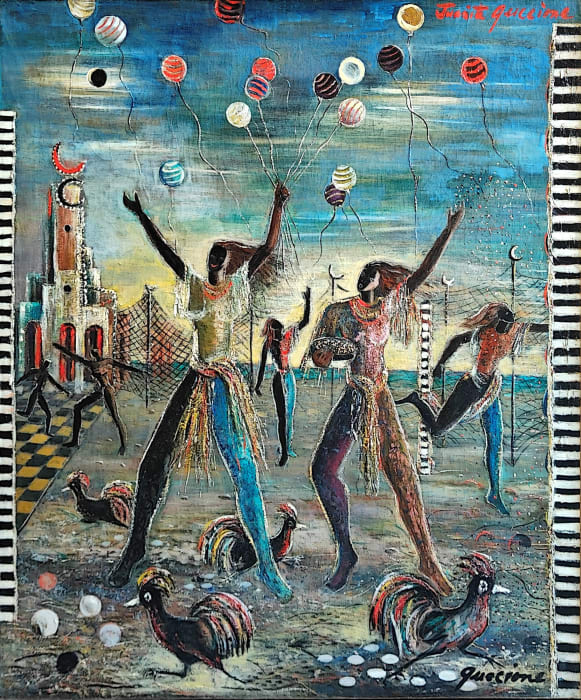

Women with Roosters and Balloons, circa 1948-52

Women with Roosters and Balloons, circa 1948-52

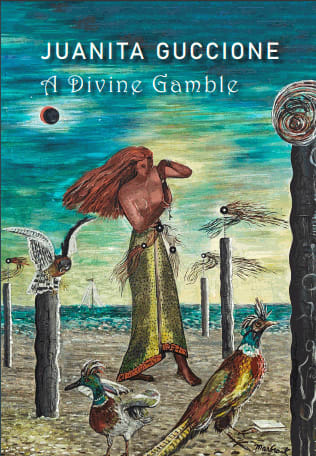

Juanita Guccione's life (June 20, 1904–December 18, 1999) spanned all but four years of the 20th Century. Cubist, realist, abstract, surrealist, and abstract surrealist strains are all to be found in her work, but by 1970 she was painting electrifying works in watercolor and acrylic that elude the most considered categorization. For the better part of her career she had been imperceptively referred to as a surrealist, but her later work abandoned the human figure and the observed world. This later work, lyrical and astral, reflected a painterly independence hinted at earlier in her career.

In the spring of 2004 the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria acquired a large number of works she had painted in Algeria in the early 1930s. These paintings are now in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Algiers. It is believed that she is the first American woman artist to be so singularly honored by a Muslim nation. Guccione, then painting as Nita Rice, lived for four years among the Ouled Nail Bedouin tribe in eastern Algeria. Her paintings from this period are devoid of the flamboyant romanticism of the Orientalist painters. She painted the Bedouin as friends and neighbors, reflecting the anti-colonialist attitude of her native land. These paintings were shown in The Brooklyn Museum in 1935, receiving a good deal of press attention.

When she returned from Algeria in 1935 the United States was in economic free fall. After the Brooklyn Museum exhibit, this work was then shut away as she immersed herself in an avant-garde then fomenting revolutionary artistic changes.

Guccione began painting as Anita Rice, then changed her name to Juanita Rice, then Juanita Marbrook, and finally to Juanita Guccione after marrying in the mid-1940s.

Guccione worked with Mexican social realist painter David Alfaro-Siqueiros on Post Office murals for the federal Works Progress Administration during the 1930s. During World War II she came under the influence of the refugee French surrealists. She studied with Hans Hofmann for seven years. Hofmann expressed high regard for her work and gave her a number of scholarships. Her mid-career surrealist paintings do not share the literary interests of many of her European contemporaries. They reveal a magical and whimsical world ruled by women. Their brilliant palette, if not their subject matter, suggests Hofmann's influence. It is in these paintings that she expresses her lifelong defiance of convention and vogue.

Guccione's exhibitions characteristically received respectful attention. Her work was shown in Manhattan, Paris, Beirut, Bombay and San Francisco. But she was unusually reclusive, and this trait often thwarted enthusiasts attempting to promote and celebrate her work. Her reclusiveness, her name changes, and the critics' difficulty in characterizing her work deprived her of the recognition she might otherwise have received. Nonetheless, the respected French critic Michel Georges Michel wrote in the early 1950s that she was one of a very few American artists who interested him, this at a time when abstract expressionism was the rage and America was establishing its claim to importance in tastemaking.

Describing her long career, the Washington Post art critic Michael Welzenbach wrote in 1992: "This kind of artistic evolution hardly fits into the inimically popular contemporary trend of modifying one's style to keep abreast of fashionable changes in the mainstream art world. And it is precisely this single-minded approach to her work, this willingness to follow its development wherever that might lead, that locates Guccione squarely among the few but formidable ranks of the modernist avant-garde—a group whose integrity and vision will not be seen again in this century."

No one, probably not even Guccione, reckoned how restless her career had been until her works were collected after her death. Her work had always been bold and challenging, but her reputation had come to rest on the surrealist oils of her middle years, while the more productive and adventurous acrylic and watercolor work of her later years was little known.

The extraordinarily reticent artist hinted at her own view of her later work when she wrote to a purchaser that she did not imagine the work, she saw it.

Guccione was a gifted teacher, perhaps because of her reticence. She was able to impart ideas and techniques by guiding her students' hands, by working alongside them, rather than lecturing them. Her appreciation of painterliness was intense.

The large body of work she left poses a significant challenge to fellow artists, curators and historians, and indeed a special challenge to feminists because she created in her middle years a peaceable otherworld ruled entirely by women.

Of feminists she was fond of remarking, "I'm not at all interested in what they say, only in what they do."

-

What to See in N.Y.C. Galleries in February

Martha Schwendener, The New York Times, February 20, 2025 -

Lincoln Glenn Gallery Rediscovers American Art That Time Forgot

Gallerists Douglas Gold and Eli Sterngass tell us how they uncover lost treasures by stellar artists from the past 160 years.Trent Morse, Introspective Magazine, November 10, 2024