Works

Biography

Everett Shinn, a future member of the Eight and remarkable, rather theatrical personality was born at Woodstown, New Jersey in 1873. Even more recent sources give 1876 as the year of Everett Shinn's birth but the artist usually lied about his age to appear younger than he actually was. Edith DeShazo claimed that information from family members established the date of November 6, 1876 as Shinn's birthday. But if this is true, he would have enrolled at the Spring Garden Institute in Philadelphia to study industrial art at the age of twelve. Born to a Quaker named Isaiah Conklin Shinn and Josephine Ransley Shinn, Everett was their third child. He enjoyed a happy childhood as an undisciplined boy fond of sweets, acrobatics, and the circus.

Shinn opted for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for instruction in the fall of 1893, and began as a staff artist for the Philadelphia Press. At that time William Glackens was working there as well, while John Sloan was at the Inquirer. A year later, Glackens was at the Press, and also, in 1894, George Luks joined the staff there. As DeShazo explained, "the Press art department became a meeting place for men both on the staff and off with similar artistic and literary interests." Members of the same group also met at Robert Henri's studio. By 1897, Shinn was in New York, working for the New York World where Luks had been for about a year. The rest of the "Philadelphia Four" would follow them before long.

Shinn spent much of 1898 hounding the offices of Harper's until finally, the editor and publisher, Colonel George Harvey saw his portfolio, then commissioned a view of the Old Metropolitan Opera House in a snowstorm. The pastel appeared about a year later in the February 17th issue of Harper's Weekly, in 1900. Meanwhile, Shinn kept busy with decorative work (murals, screens, and door panels) at private residences and even in Trenton, New Jersey's City Hall. In 1899, the Boussod-Valadon Galleries gave Shinn his first one-man show. He continued to carry out commissions for illustrations. Shinn began exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy (1899-1908) and at the Art Institute of Chicago (1903-43).

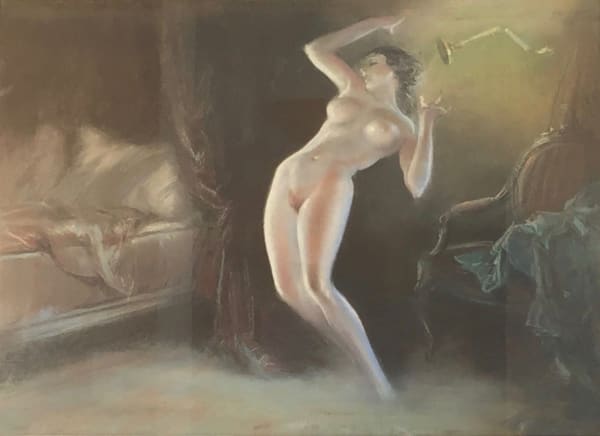

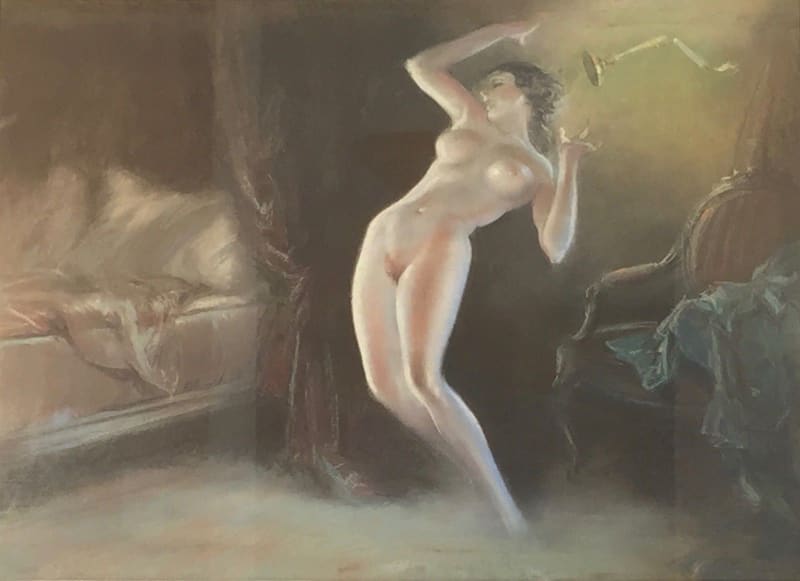

A trip to Europe is documented in 1900 by an exhibition at Goupil's in Paris and by various drawings of Paris and London but nothing more appears to be known about where Shinn went or what he saw, except that he was in Paris in July. Undoubtedly, he would have seen the art at the Paris Universal Exposition. DeShazo noted that after having returned to America, Shinn lost interest in lower class urban life, and Young pointed out that unlike most members of the Eight, Shinn was not attracted to art focused on "people sleeping under bridges." In fact, he loved the glamor of Uptown, fashionably dressed ladies, and above all, Shinn wanted to depict the excitement of the theater. He himself was an amateur playwright. Shinn used spatial devices that Degas had initiated earlier but as Young rightly observed, Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931) is a more accurate source for Shinn's chic theatrical pieces, dancers, and cabaret scenes. Théophile Steinlen (1859-1901) was another artist popular with the Philadelphia artist-reporters group, as Ferber noted.

Shinn was not part of the National Arts Club exhibition of works by future members of the Eight in 1904, but he was mentioned by Gallatin in 1906 as a kind of American Degas. The author praised Shinn's draftsmanship and the technique of his pastels: "Very real they are: we might almost imagine ourselves looking in upon the actual scene." Shinn did take part in Macbeth Galleries' famous show four years later. He exhibited eight works, including The Hippodrome, London (Art Institute of Chicago), The White Ballet, ca. 1905, and The Orchestra Pit (both: collection of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur G. Altschul). One of his works sold, a painting now called Revue (Whitney Museum of American Art), formerly titled Girl in Blue. Shinn also participated in the Exhibition of Independent Artists in 1910 and finished the murals in Trenton in the following year. Milton Brown regarded these depictions by Shinn of pottery kilns and steel mills as "important . . . in that they treated a contemporary industrial subject rather than an historical or allegorical scene."

Shinn was invited but refused to exhibit in the 1913 Armory Show. In fact, at that time, he was working on neo-Rococo decorative panels in private residences. Not much has been written on Shinn's activities between 1920 and 1940. He did not exhibit often but continued to work as an illustrator. In the 1940s, Shinn was represented by Ferargil Galleries. He contributed "Recollections of The Eight," an essay in the Brooklyn Museum's catalogue of the exhibition The Eight, which opened on 24 November 1943. The rather monochromatic Washington Square (Addison Gallery of American Art) is a late work, from around 1945. Shinn, who died in New York City on May 1, 1953, managed to outlive all other members of the Eight. Unfortunately for us all, a thorough, scholarly monograph on the artist remains to be written. Shinn showed the impressionists' love of contemporary subject matter and painted in a spontaneous, non-academic manner. In fact, critics seem to agree that Shinn's facility was his downfall. On the other hand, he maintained visual and narrative clarity, as his penchant toward illustration prevailed.

Shinn opted for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for instruction in the fall of 1893, and began as a staff artist for the Philadelphia Press. At that time William Glackens was working there as well, while John Sloan was at the Inquirer. A year later, Glackens was at the Press, and also, in 1894, George Luks joined the staff there. As DeShazo explained, "the Press art department became a meeting place for men both on the staff and off with similar artistic and literary interests." Members of the same group also met at Robert Henri's studio. By 1897, Shinn was in New York, working for the New York World where Luks had been for about a year. The rest of the "Philadelphia Four" would follow them before long.

Shinn spent much of 1898 hounding the offices of Harper's until finally, the editor and publisher, Colonel George Harvey saw his portfolio, then commissioned a view of the Old Metropolitan Opera House in a snowstorm. The pastel appeared about a year later in the February 17th issue of Harper's Weekly, in 1900. Meanwhile, Shinn kept busy with decorative work (murals, screens, and door panels) at private residences and even in Trenton, New Jersey's City Hall. In 1899, the Boussod-Valadon Galleries gave Shinn his first one-man show. He continued to carry out commissions for illustrations. Shinn began exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy (1899-1908) and at the Art Institute of Chicago (1903-43).

A trip to Europe is documented in 1900 by an exhibition at Goupil's in Paris and by various drawings of Paris and London but nothing more appears to be known about where Shinn went or what he saw, except that he was in Paris in July. Undoubtedly, he would have seen the art at the Paris Universal Exposition. DeShazo noted that after having returned to America, Shinn lost interest in lower class urban life, and Young pointed out that unlike most members of the Eight, Shinn was not attracted to art focused on "people sleeping under bridges." In fact, he loved the glamor of Uptown, fashionably dressed ladies, and above all, Shinn wanted to depict the excitement of the theater. He himself was an amateur playwright. Shinn used spatial devices that Degas had initiated earlier but as Young rightly observed, Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931) is a more accurate source for Shinn's chic theatrical pieces, dancers, and cabaret scenes. Théophile Steinlen (1859-1901) was another artist popular with the Philadelphia artist-reporters group, as Ferber noted.

Shinn was not part of the National Arts Club exhibition of works by future members of the Eight in 1904, but he was mentioned by Gallatin in 1906 as a kind of American Degas. The author praised Shinn's draftsmanship and the technique of his pastels: "Very real they are: we might almost imagine ourselves looking in upon the actual scene." Shinn did take part in Macbeth Galleries' famous show four years later. He exhibited eight works, including The Hippodrome, London (Art Institute of Chicago), The White Ballet, ca. 1905, and The Orchestra Pit (both: collection of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur G. Altschul). One of his works sold, a painting now called Revue (Whitney Museum of American Art), formerly titled Girl in Blue. Shinn also participated in the Exhibition of Independent Artists in 1910 and finished the murals in Trenton in the following year. Milton Brown regarded these depictions by Shinn of pottery kilns and steel mills as "important . . . in that they treated a contemporary industrial subject rather than an historical or allegorical scene."

Shinn was invited but refused to exhibit in the 1913 Armory Show. In fact, at that time, he was working on neo-Rococo decorative panels in private residences. Not much has been written on Shinn's activities between 1920 and 1940. He did not exhibit often but continued to work as an illustrator. In the 1940s, Shinn was represented by Ferargil Galleries. He contributed "Recollections of The Eight," an essay in the Brooklyn Museum's catalogue of the exhibition The Eight, which opened on 24 November 1943. The rather monochromatic Washington Square (Addison Gallery of American Art) is a late work, from around 1945. Shinn, who died in New York City on May 1, 1953, managed to outlive all other members of the Eight. Unfortunately for us all, a thorough, scholarly monograph on the artist remains to be written. Shinn showed the impressionists' love of contemporary subject matter and painted in a spontaneous, non-academic manner. In fact, critics seem to agree that Shinn's facility was his downfall. On the other hand, he maintained visual and narrative clarity, as his penchant toward illustration prevailed.

Exhibitions

Publications

Events

Enquire