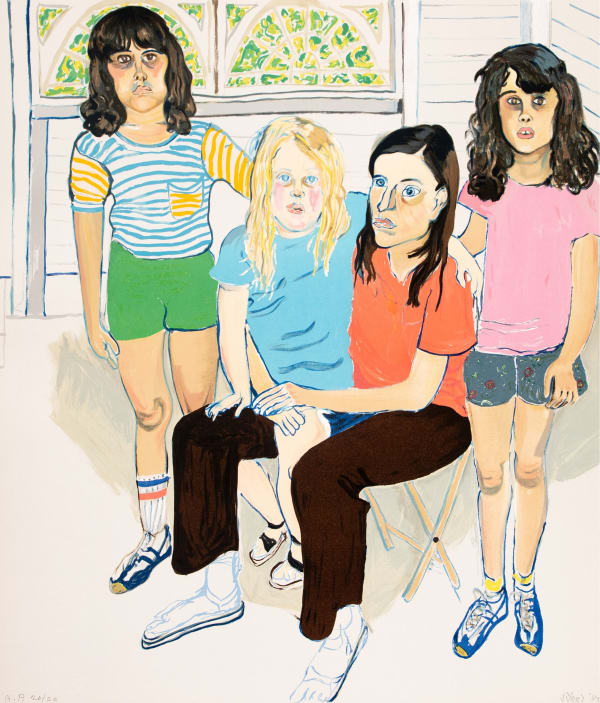

The son of Greek immigrants, Theodoros Stamos was a first-generation member of the influential New York School of modern artists. The youngest of that cohort of Abstract Expressionists—which included Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko—Stamos was a devoted practitioner who continued to explore shape and color into the movement’s maturation in the second half of the twentieth century. Unlike many Abstract Expressionists who took an improvisational approach to their compositions and execution, Stamos always carefully controlled his paint, harnessing what he believed to be an artist’s “spiritual power, which communicates life and meaning to material form.”

The native New Yorker was precocious, enrolling at the age of thirteen at the American Artists School. He initially studied sculpture, but soon switched to painting and was basically self-taught. He regularly visited the city’s galleries and came to admire the work of Arthur Dove and Milton Avery. Stamos’ painterly talents were soon recognized by such pivotal figures as Betty Parsons, who began to exhibit his work in 1943, and by the Whitney Museum of American Art, which included him in its 1945 Whitney Biennial. Much of his early work consisted of biomorphic forms inspired by his many visits to the Museum of Natural History. An inveterate traveler, Stamos visited his ancestral homeland in 1948 and was captivated by the light and intense colors of the Greek landscape.

The year 1950 was a high point for the artist. The Phillips Gallery in Washington, DC, renowned for its collection of works by Dove, hosted a solo exhibition of Stamos’ paintings. That year also marked the first of four summers Stamos spent teaching at Black Mountain College. Enthralled by the North Carolina countryside, he turned to landscape-derived imagery, later recalling: “My studio looked over some beautiful farmland and mountains that were almost always shrouded in veils of mists.” While at Black Mountain, he met the influential art critic Clement Greenberg. An advocate of Abstract Expressionism who had the power to make or break careers, Greenberg once published a negative review of Stamos’ work. Years later, Greenberg recognized Stamos’ import and retracted his earlier opinion: “I scorched his show and I was wrong.”

In May 1950, Stamos joined other avant-garde artists in a protest against the Metropolitan Museum of Art, accusing it of a conservative and outmoded attitude toward contemporary American art. The January 1951 issue of Life featured an infamous photograph of eighteen artists, whom the magazine labeled “The Irascibles.” Stamos sat in the front row along with Mark Rothko, who became a lifelong friend. The pair’s painting was similar in style: large format spans of color with soft edges that are bled into the canvas. After Rothko committed suicide in 1970, Stamos served as an executor of his estate and was later embroiled in a multi-million dollar lawsuit that, for a time, tarnished his reputation.

Stamos joined the faculty of the Arts Students League in 1955 and remained an instructor there for twenty-two years. He continued to travel extensively and created series based on several sites including Jerusalem, Delphi, and Lefkada, an island in the Ionian Sea.

-

150 Years of Influential Instructors

Historical Teachers at the Art Students League January 16 - February 28, 2025 Upper East SideRead more -

The Inaugural Show

A Century in American Art May 3 - September 3, 2022Lincoln Glenn is proud to invite you to its inaugural exhibition at 126 Larchmont Ave. This first exhibition will be a sample of the gallery's inventory, representing over 100 years...Read more